The Burdick Murder - Part Two - The Affair

By early 1898, there were signs that something was not quite right with Alice and Edwin Burdick’s marriage.

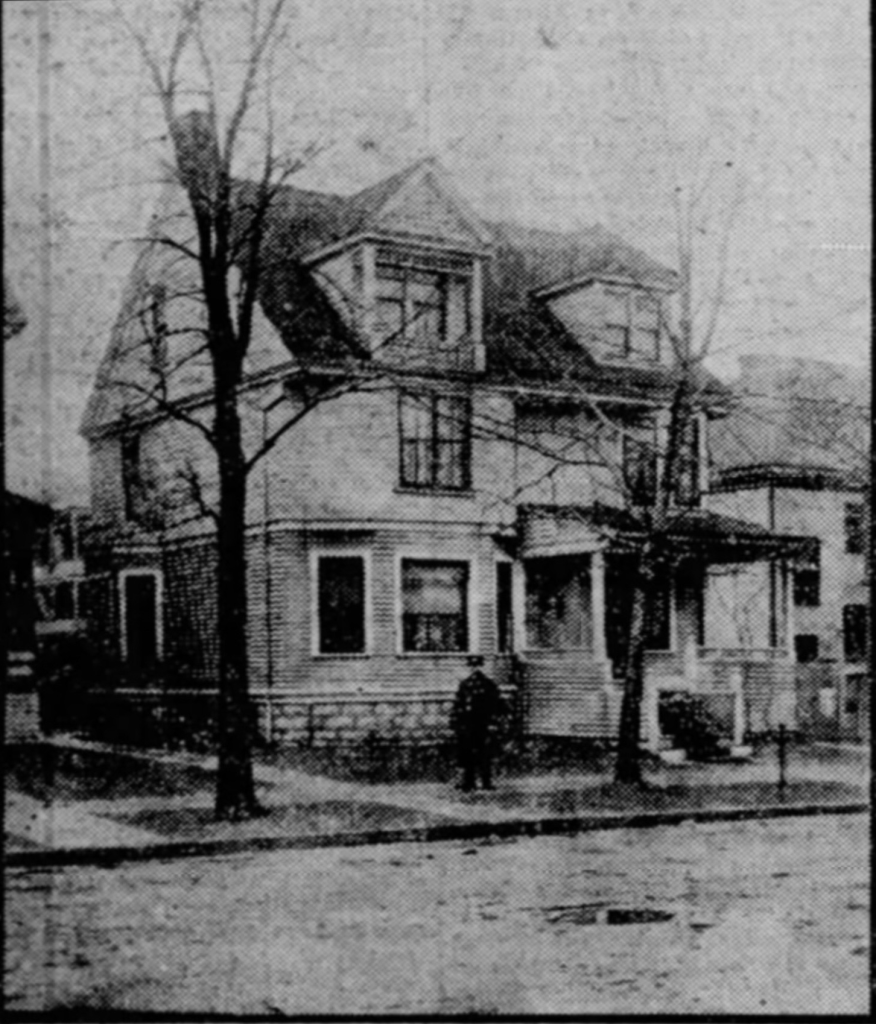

Screaming matches were occasionally heard in the vicinity of the family home at 101 Ashland—one even spilling out onto the sidewalk. After a particularly bitter quarrel, there was talk that Allie had bashed Ed over the head with a chair, requiring him to wear a conspicuous bandage on his noggin. Yet all this was only a foretaste of things to come.

Arthur Reed Pennell, circa 1898. Public domain.

Carrie Lamb Pennell, circa 1898. Public domain.

The final fuse was lit at a euchre party on the evening of March 6, 1898, at the 320 Richmond Avenue home of Elmwood Set members Mr. & Mrs. Elmer Fisher. Joining Ed, Allie, and the Fishers for the game were two newcomers to the Set—Arthur Reed Pennell and his wife, Carrie Lamb Pennell, of 208 Cleveland Avenue.

208 Cleveland, circa 1903. 1903 image public domain.

Modern image author’s collection.

Arthur and Carrie Pennell seemed to have it all. Carrie was the daughter of a wealthy New Haven family, and Arthur, a Mainer, was the son of a sea captain. Both were college graduates—Carrie from Wellesley and Arthur from Yale and then Yale Law. In Buffalo, Carrie was prominent in the Wellesley Club, the DAR, and many other causes. In addition to his Ivy League pedigree, Arthur could boast dashing good looks and the muscled physique of the champion single-scull rower he had been while at Yale. He was also highly intelligent, very much a free-thinker, and—in recent times at least—seemed to be living a life of independent leisure.

This last item was something of a mystery, since for years he had been working steadily with his best friend from college days, Thomas J. Penney. Upon graduating from Yale Law in 1889, both Pennell and Penney did what many young, ambitious men did in those days—they came to Buffalo to make their fortune. They set up a two-man law practice focusing mainly on real estate transactions, a partnership that lasted until late 1895, when Penney was named Erie County’s Assistant District Attorney.

Arthur Pennell had to strike out on his own. For a while, his name still appears in court records, although soon he vanishes entirely and seems to have lacked for work. Even as his previous source of income dwindled, about this time Arthur began living large—very large. Friends noticed that while Arthur had long been a fan of the quick, fifty-cent ($2.50 today) lunch specials offered at downtown restaurants, at some point after 1895 he began enjoying multi-hour, multi-course luncheons that cost as much as five dollars ($250). It was also noticed that he was rarely in his Austin Building law office, and never in court. When new cases came to him by happenstance, he fobbed them off on friends in the Bar Association.

He also began traveling frequently to New York, sometimes with Carrie and sometimes alone, preferring to stay at the Waldorf, the Hoffman House, or another of New York’s finest and most expensive palace hotels. Back home, between lounging and lunching he found time to pay off his mortgage in a lump sum and regularly made large deposits at the bank, although tellers were confounded that each was made up of a mass of coins and dirty, crumpled banknotes.

He bought a racing bicycle, a German precision microscope, and a Buffalo Electric automobile—the last a custom, $2,000 machine ($100,000 today). Word around Elmwood was that the Pennells were ‘going through at least $20,000 a year’ (about $1 million today).

Where all this money came from, and so suddenly, no one knew. Arthur would say only that had begun managing the financial matters of several prominent New England families, but would provide no specifics.

Arthur Pennell’s electric automobile; on right the only known example (in the Pierce-Arrow Museum)–not the Pennells’, but the same model. List price was $1,650, and Arthur added custom monogramming and more aggressive gearing for flat-out driving (a touch over 20 mph).

By the time of the Fishers’ card party, Arthur was thirty-four years old, and Allie four years his senior. Sparks must have flown that night in the front parlor of 320 Richmond Avenue, because afterward Arthur began spending copious amounts of money—and free time—on Mrs. Burdick. While this did not go unnoticed, both parties had a semi-plausible excuse—that busy businessman Ed Burdick was happy that his wife had found a diversion in Arthur Pennell’s company. Arthur soon had the run of the Burdick house, and Ed urged their three daughters to call their new best friend ‘Uncle Artie’.

In June came the first climax. Ed encouraged Alice to spend a week traveling with Arthur and Carrie—the perfect chaperone—to Yale’s commencement exercises in New Haven, while he opted to stay behind.

Ed may well have thought that fun and frolic at the old alma mater might cause Arthur and Alice’s feet of clay to crumble completely. And on June 26, 1898, crumble they did, in spectacular fashion. On that evening, while on his way to meet his wife at an alumni ball (!), Arthur caught up with Alice in the Phelps Gateway.

He drew her into the shadows of the arch, and they kissed. And not on the cheek, mind you.

Phelps Gateway, Yale University. Author’s collection.

This first kiss was like popping a champagne cork. Over the next five years—that’s right, five years—it became embarrassingly obvious that Allie and Arthur were madly in love. They would ‘bump into each other’ on the trolley or on the sidewalk downtown, and then disappear for hours. Arthur began renting furnished rooms here and there in Buffalo for assignations with Alice. Though without any visible means of support, Arthur took a second office in the Ellicott Square Building—under the name of a phony collection business—where he and Allie could meet.

And Edwin and Alice stopped sharing a bedroom.

Arthur Pennell’s law office today (above the rear of the red car), 110 Franklin St., and in 1903. Left image author’s collection; right public domain.

One of the most peculiar elements of this story is that for quite some time neither Ed Burdick nor Carrie Pennell seemed to mind. Carrie’s reasons are murky, but her friends had noticed that she had taken a liking to Arthur’s sudden wealth and social ascent, and may have been willing to turn a blind eye to his peccadilloes in favor of the high life.

As for Ed—it may be coincidence, but just as the Arthur/Allie affair was coming to a head, he and at least two other women were linked romantically—one whose husband later drank himself to death, and another whose husband and Ed nearly came to blows over the matter. Meanwhile, Ed was playing either Good Samaritan or sugar daddy to one of his envelope makers, paying for the young lady’s lodging and expenses.

Liberty roses–Alice Burdick’s favorite flower. Author’s collection.

If an adulterous liaison between Arthur and Allie was what Ed wanted, he got his wish. The pair snuck off to Atlantic City and New York, wrote gooey love letters to each other, and were even spotted walking together in Front Park, arm in arm–a particularly brazen act at the time.

On one occasion, Arthur & Carrie hosted a birthday party for Alice Burdick, and when the Burdicks arrived, they found the entire ground floor of the Pennell house stuffed full of thousands of Liberty roses . . . Allie’s favorite flower, and in Victorian terms red roses meant only one thing: love.

You may ask why Ed didn’t file for divorce and be done with it. Simple: Until 1966, adultery was the sole grounds for divorce in New York State. And so if you wanted to discard an unwanted spouse, he or she would have to commit provable adultery, or you were stuck. And so Ed’s enthusiasm for Arthur Pennell’s courting of Alice Burdick was potentially part of a plot to dispose of her legally and keep both 100% of the couple’s growing assets and at least partial custody of the children. This hypothesis is supported by contemporaries in the Elmwood Set, who commented (and later testified under oath) that Ed Burdick had ‘done everything he could to put Allie and Arthur together’.

After a while, though, Ed found himself immersed in a full-blown scandal–the greatest fear of any respectable Gilded Age family. Friends began urging him to stop being a cuckold (his own possible affairs notwithstanding), acquire some hard evidence of adultery–walking arm in arm was scandalous, not adulterous–and file suit for divorce. At last, Ed hired a team of private detectives to photograph his wife’s comings and goings and to ‘sweat’ Arthur. Soon thereafter, Uncle Artie became persona non grata at the Burdick home.

All this rankled with Arthur, who seemed to think he had done nothing wrong and deserved no such censure. Why, Ed had gone to absurd lengths to encourage feelings to develop between him and Alice—what did he expect?—and if there’s one thing we can say about Arthur Reed Pennell, it’s that he was proud, vain, and possessed of a brooding and intense emotional makeup. He did not appreciate being made a patsy by another man seeking a divorce, and he was not about to be beaten at this or any other game by a pipsqueak nobody like Eddie Burdick from Lenox, New York.

Things were about to get very, very ugly.

Up Next: War (Part Three)