The Camera Crusader

Meet Lodowick “Loddy” Holmes Jones—attorney-at-law, moral crusader, and collector of enemies.

Many a mystery swirls around this colorful fellow, whose equally colorful name is an old variant of ‘Ludwig’. Loddy was born into a prominent Buffalo family, grew up at 283 Linwood Avenue, and graduated from Central High School in June 1895.

Three years later, he appears in the Buffalo papers as a ‘young attorney’—a remarkably short course of study, even then. (In addition to being a quick learner, Loddy was also a very snappy dresser. In a time when most men (and certainly most attorneys) wore staid shades of grey, Loddy sported suits, shoes, and caps of brilliant white duck; pink shirts with blue collars, and—gasp!—green neckties. He must have looked something like an ice-cream vendor, but with more panache.)

Consistent with his sartorial derring-do, L. H. Jones, Esq. also seemed to possess some other equally smart-alecky tendencies: a hunger for attention, even if negative; a penchant for poking the powerful in the eye; and (the sum of the other two) a natural talent for manufacturing enemies.

Exhibit One: Loddy picked his first-ever legal fight with all of Buffalo by attempting to ban Sunday baseball games, which he considered inappropriate for the Sabbath. (Baseball was the sports obsession of the time, and to put this into a modern context—Loddy’s action would be akin to someone today filing an injunction to prevent the Bills from playing on Sunday. Imagine!)

After several attempts to dismiss him as a crank, Police Justice King had at last to hear Loddy’s case against baseball. King listened with barely concealed contempt and then proceeded to bellow at the young man that it was ‘a heckuva lot better to play ball on a Sunday than go out and get drunk!’. The judge threw the case, and Loddy, out of his court—with a few choice parting words about appropriate courtroom attire.

Undeterred, our young Don Quixote commenced tilting at other windmills: boxing matches, vaudeville shows, and anything else that seemed, well, unseemly. But nothing quite clicked until he turned to a popular target: the so-called ‘Raines Law hotels’—flophouses that were permitted to serve alcohol on Sundays. The apparently fearless Loddy took to carrying a Kodak Brownie camera with him into the Tenderloin, one of Buffalo’s two (tolerated) vice districts.

(Buffalo’s Tenderloin, named after the great original in New York City, was a trapezoidal area bounded by Washington, Exchange, and Michigan Streets, and topped at an angle by Broadway. Much more to come on the Tenderloin—a hive of Gilded Age mystery!—and the hopelessly ill-conceived Raines Law.)

Lurking around corners and in alleyways, Loddy would lie in wait for drunken men or brothel clients to emerge from their boltholes—and then leap out of concealment and snap their photographs. This candid-camera business earned him the nickname ‘Kodak’ Jones—and also a half-dozen tutorial beat-downs, several smashed cameras, and a legion of enemies.

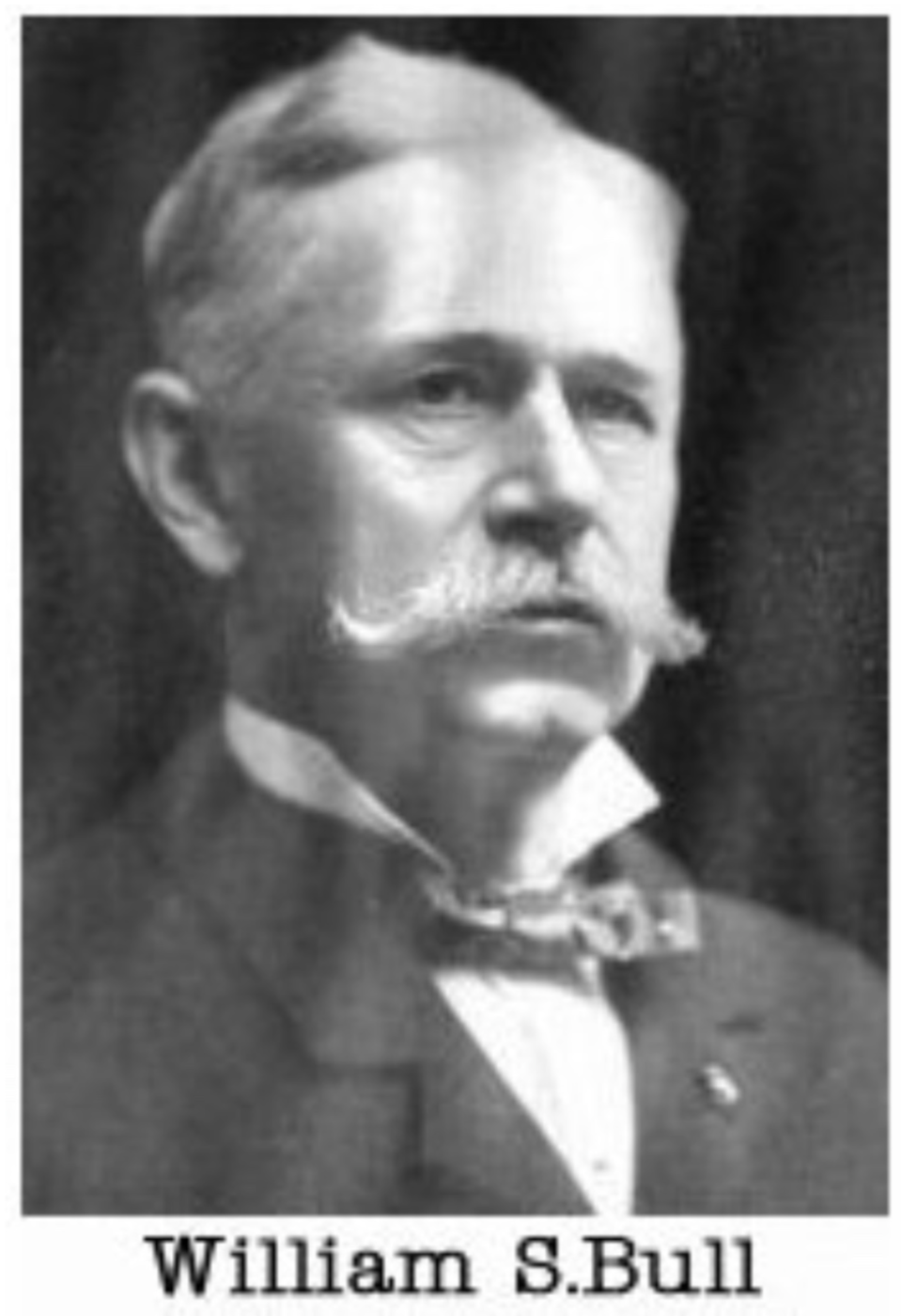

One particularly powerful enemy was the aptly named Police Superintendent General William Bull. Bull, a decorated Civil War officer (after the war rising to brigadier general in the National Guard), was not a man to be trifled with—except by our young attorney. Never one to pass by a perfectly good hornet’s nest without giving it a whack, in 1898 Loddy sued General Bull and his entire department for ‘dereliction of duty’—their presumed failure to stop the (technically) illegal vice trade in the Tenderloin. This lawsuit, too, was hurled thunderously out of court by Police Justice King, but not before earning Loddy the lasting enmity of the Buffalo Police Department. Here’s a picture of Bull at the time (be honest, would you cross that man? I would not.)

Soon after, it came out that ‘Kodak’ Jones’s exploits on behalf of right-vs-wrong had been bankrolled by two big charities: the Anti-Saloon League and the Reform Union. It wasn’t (and still isn’t) cheap to be a crusader, though, so when the charities’ bank accounts ran dry, Loddy reappeared in the newspapers, asserting that ‘Reform Doesn’t Pay!’. He then took to defending the very saloon keepers, brewers, pimps, and johns that he had been hauling into court only a week before

(For a fellow named after a camera, Jones seems to have been extremely camera-shy. Although he made the papers hundreds of times, I have found only two photographs of the man–both of which are in this post.)

Apparently in his attempts to squelch boxing matches in Buffalo, he fell in love with the sport. (Above, inset – Loddy is on the right.)

And here is Loddy in rather conservative dress.

In 1902 he married, and it seemed that our young maverick would settle down. But within a year of the nuptials, Loddy abruptly blew town, leaving behind his new bride Rena—and $498,607 (almost $25 million today!) in debt, owed to a number of very angry creditors.

It took two years for detectives to track him to a shabby apartment in New York City, where he was living under the slightly self-defeating alias of ‘Mr. Holmes Jones’. With claimed assets of only $140, Loddy immediately declared bankruptcy—and immediately vanished again. He re-emerged ten years later, this time in Baltimore, where he and Rena (presumably reconciled) welcomed a son.

Despite having become a kind of pariah in Buffalo, Loddy apparently couldn’t resist the Queen City. Sometime around 1915, he began sneaking back (solo) to the city, staying in a house at 249 Elmwood Avenue. Why? Who knows. We know that he didn’t visit his parents at 283 Linwood, because they told the newspapers in 1922 that they hadn’t seen their son for at least a decade.

These periodic visits went on for seven years, while Rena and their son remained in Maryland. But at last either Loddy’s luck ran out, or his enemies caught up to him. Very late in the evening of September 6, 1922, at the corner of Elmwood Avenue and Chippewa Street, a witness claimed to have seen Loddy intervene (naturally) in a ‘gang fight’ that had broken out over an automobile collision. Several hours later, Loddy was found lying face down in the street near the scene. He was taken to Columbia Hospital, where he died shortly after midnight, without ever regaining consciousness.

The subsequent police inquest was lukewarm. The ‘gang’ was never identified, and who or what had bashed in Loddy’s head remains a mystery. Yet the Police Department’s tepid interest in Loddy’s death—or very possibly murder—was probably in keeping with the bad blood of two decades earlier.

And with that, the earthly remains of Lodowick ‘Kodak’ Holmes Jones, Esq., were interred in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Section D. His wife and son never did join him, but you can visit if you like.

I suspect Loddy would welcome the attention.