Ask Me Anything: Gilded Age Thanksgiving

Ask Me Anything: Gilded Age Thanksgiving Edition

What did Thanksgiving look like in the decades of opulence, rapid industrialization, and spirited social change known as the Gilded Age (roughly 1870–1905)?

Thank you to all of you who sent in your questions. Read on for my answers!

Did people decorate for Thanksgiving?

Yes, and lavishly, if they could. Gilded Age Thanksgiving décor revolved around a harvest theme and relied heavily on natural, seasonal materials. Chrysanthemums, asters, and marigolds dominated with their vivid autumn colors. Wealthy hosts also added roses and ferns, which were subtle displays of status that signaled access to hot-house floriculture.

Dried grasses, grains, colorful foliage, pinecones, nuts, berries, fruits, and vegetables often formed abundant, overflowing centerpieces. Circular arrangements were fashionable, and the cornucopia, the “Horn of Plenty," served as a symbolic centerpiece of prosperity, filled to bursting with flowers and produce.

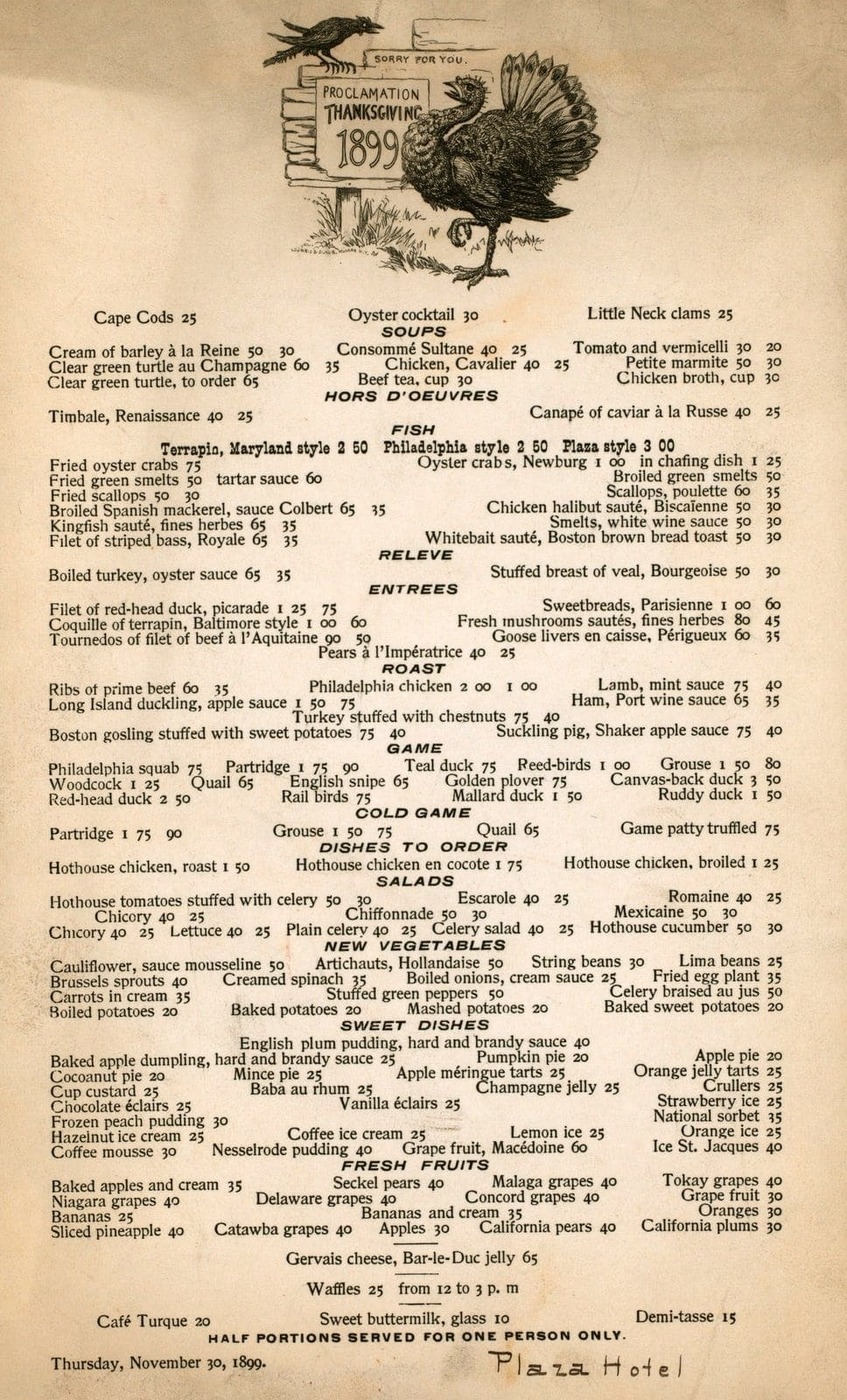

What was a typical Thanksgiving menu?

Turkey was already the centerpiece, but a Gilded Age feast was far more elaborate than the modern meal. Wealthy households and hotel dining rooms served multi-course spreads heavily influenced by French cuisine. A single menu might include:

- Oyster soup (oysters were cheap and plentiful before overharvesting)

- Celery salad (celery was a luxury; glass celery vases became fashionable)

- Fricasseed chicken, venison, or duck, in addition to turkey

- Sweetbreads, a classic 19th-century delicacy

- Charlotte Russe, plum pudding, or towering sponge cakes

- Cranberry sauce, increasingly available thanks to industrial canning

Holiday menus printed in newspapers often read like edible status symbols, and advertising refinement, cosmopolitan tastes, and social standing.

How did people entertain themselves on Thanksgiving?

Long before the Macy’s Parade (1924), cities held local Thanksgiving parades and “ragamuffin” processions, where children in costumes roaming the streets demanding treats. Newspapers of the 1890s called it “an annual public nuisance,” but children adored the chaos.

At home, entertainment was charmingly analog: parlor games, piano music, amateur theatricals, and family read-aloud sessions from poetry or popular fiction.

Football, too, was already part of the cultural landscape. Elite college teams—most famously Harvard and Yale—played annual Thanksgiving Day games starting in the 1870s, turning the match into a major social event.

Did people travel for Thanksgiving?

Yes, though not in the massive, synchronized waves we know today. By the 1880s, expanding railroad networks made regional travel easier, allowing college students to head home and families to reunite across states. Still, Gilded Age holiday travel was far more modest than the modern Thanksgiving exodus.

Were there political fights at the dinner table?

Absolutely. The Gilded Age was politically combustible: debates over monetary policy, labor rights, immigration, temperance, and tariffs filled newspapers and dinner tables alike. One paper joked about “the annual carving of the turkey and of one’s relatives’ opinions”—proof that contentious holiday conversations are nothing new.

Were cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie already common?

Yes. Pumpkin pie was nearly universal by the late 19th century, and cranberry sauce—homemade or newly available in commercial form—was a holiday standard. Industrial canning made cranberries widely accessible by the 1890s, though the familiar jellied log was still decades away.

Focus on Thanksgiving foods?

Why oysters?

They were abundant, inexpensive, and a hallmark of formal American meals before overharvesting depleted oyster beds.

Why so many courses?

French culinary influence was at its height. Even middle-class hosts aspired to multi-course “company dinners.”

Was turkey alone?

Not at all. Goose, beef, venison, and duck often appeared; abundance was part of the performance.

Why the elaborate desserts?

Late Victorian and Edwardian taste favored puddings, molded desserts, and whipped-cream confections—sweet, ornate, and theatrical.

Did people dress up for Thanksgiving?

In wealthy families, Thanksgiving dinner was a semi-formal event. Women wore visiting gowns while men appeared in suits or evening wear. Middle-class families aimed for neat respectability, while working-class families focused on practicality. And children participating in ragamuffin parades often wore intentionally ragged clothing to beg for treats.

Did the Gilded Age have “kids’ tables”?

Short answer: Yes—but not quite the way we picture them.

Notably, people of the era would have said children, not kids, which referred to young goats. Manuals often scolded adults for using the wrong word.

In wealthy households, separate children’s tables were the norm. In upper-class homes with servants, children typically ate in another room or at a smaller table. Etiquette dictated that they not interrupt formal dining rituals, and servants oversaw their meal. This wasn’t seen as dismissive; it was considered proper upbringing.

In middle-class families, a children’s table might or might not appear. Space dictated arrangements more than etiquette. Children might eat at a sideboard or smaller table, while older children often joined adults. The children’s table, if present, was simple—plain cloth, basic cutlery, smaller portions, no whimsical decorations.

In working-class homes, separate dining spaces were uncommon. Families ate together, and informality prevailed.

What etiquette rules shaped a Thanksgiving dinner?

Gilded Age Americans took etiquette seriously. Household manuals were popular, and hosts and guests were expected to follow clear social codes.

Expectations for Hosts

- Invitations: Wealthy families used printed cards; middle-class hosts invited guests verbally about a week in advance.

- The hostess set the tone: She was expected to appear calm, gracious, and never flustered by kitchen work.

- The table as a showpiece: Basics such as a white damask cloth, polished silver, sparkling glass, simple napkin folds, and a centerpiece signaled refinement.

- Strategic seating: Planned in advance to separate quarrelsome relatives, balance personalities, and honor prominent guests.

- Carving mattered: The host—or a chosen gentleman—carved the turkey with practiced elegance.

- Courses moved at a measured pace: Oysters → soup → fish → entrées → roasts → vegetables → salad → desserts → fruit and nuts → coffee.

- Portions stayed modest: Guests followed the hostess’s lead, and choosing smaller portions of each course.

- Avoiding controversy: The hostess steered conversation away from politics, religion, and labor disputes—though not always successfully.

Expectations for Guests

- An accepted invitation was binding: Canceling was a notable offense.

- Punctuality was essential: Arriving late insulted the hostess and disrupted the meal’s timing.

- No hostess gifts: Bringing food or wine implied the hosts were unprepared. The exception: flowers sent earlier in the day.

- Dress appropriately: Formality matched the hour and the household.

- Follow the hostess’s cues: Guests waited for their hostess to begin eating.

- Conversation: Light and polite. Safe topics included weather, books, and travel.

- Thanks and timely departure: Guests expressed gratitude briefly and did not linger excessively.

Thanksgiving in the Gilded Age blended tradition with theatricality. It was a day of abundant tables, strict etiquette, bustling parades, eager children, and menus that stretched for pages.

While our modern holiday may be more relaxed (and features more stuffing than sweetbreads), many of the rituals—travel, football, pies, and spirited family debates—would feel familiar to diners of more than a century ago.

Upscale Thanksgiving Menu

As served in an upscale hotel dining room or a well-to-do American household.

Relishes & Appetizers

Blue Point oysters • Celery hearts in glass vases • Queen olives • Pickled walnuts • Radishes • Watercress

Soups

Consommé Royale • Purée of chestnut with croutons

Fish Course

Baked salmon à la Hollandaise, garnished with cucumbers and parsley

Entrées

Sweetbreads with mushrooms • Chicken croquettes with peas • Pâté de foie gras en aspic

Roasts

Roast turkey, Maryland style, with giblet gravy and cranberry jelly

Prime ribs of beef au jus

Roast goose with apple stuffing

Vegetables

Mashed potatoes • Candied sweet potatoes • Stewed tomatoes • Succotash • Creamed onions • Buttered Brussels sprouts

Cold Dishes & Salads

Chicken salad with mayonnaise • Waldorf salad • Lettuce with French dressing

Puddings & Pastry

Plum pudding • Mince pie • Pumpkin pie • Apple tartlets • Charlotte Russe • Ladyfingers with whipped cream

Fruits & Nuts

Mixed nuts • Oranges • Grapes • Bananas • Raisins • Candied ginger

Cheeses

Neufchâtel • Edam • Roquefort

Beverages

Coffee • Tea • Hot chocolate • Cider • Claret • Madeira • Apollinaris sparkling water