Robert’s Ruminations: Interesting People who have taught me Interesting Things

I have always been curious about other people’s lives, and I suppose that is one of the characteristics of the writer. The writer has to be a student of human nature, of nature itself, and of the metaphysical realm (or what we can know about it).

I have been fortunate, blessed, or just dumb lucky to have known some interesting people over the years, and I thought I’d share with you a few of the things I’ve learned from them which continue to inform my life today. Today I’ll introduce you to two of them.

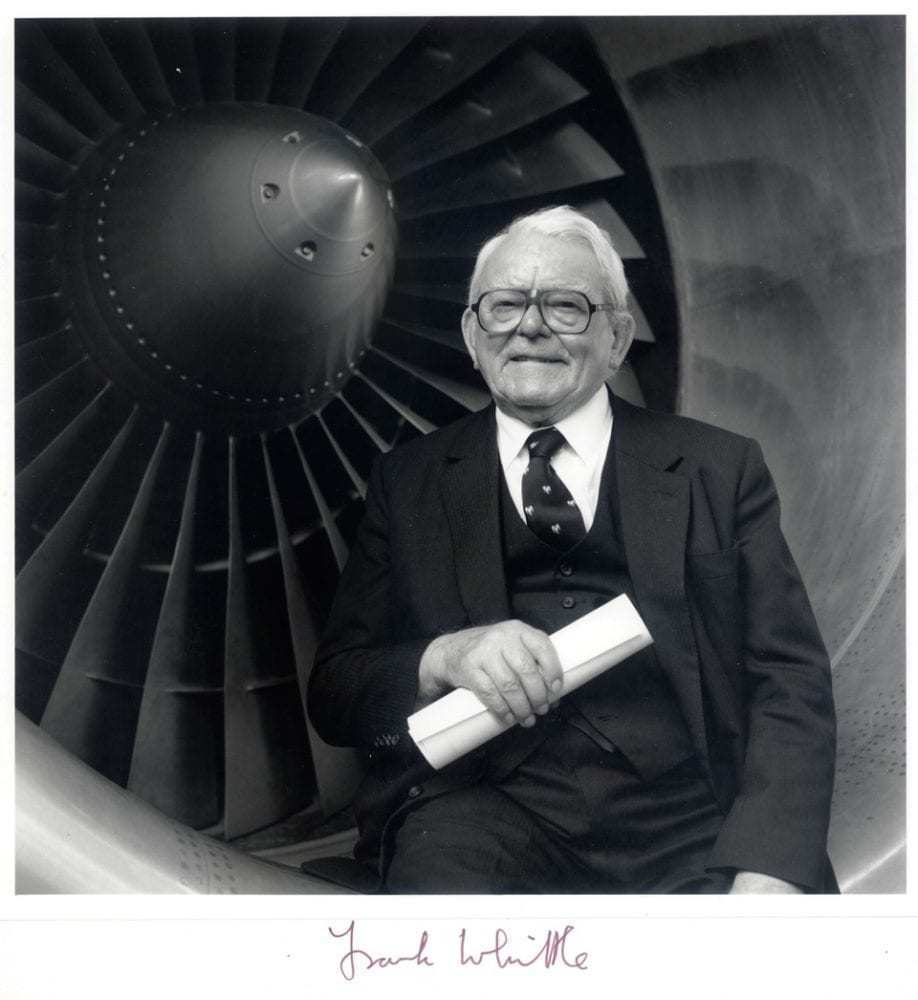

Sir Frank Whittle—Inventor of the jet engine. I met Sir Frank in 1990. Despite a 60-year age differential, for some reason the two of us hit it off, and for the next five-and-a-half years I saw him most every Sunday at his then-home in Columbia, Maryland. We became fast friends over lots of champagne and Eggs Benedict at his favorite local brunch place!

(Frank Whittle, in my opinion, deserves to be classed with Isaac Newton in the pantheon of great inventors. If you doubt me, imagine what life would be like today without the jet engine. I can’t do justice to the man in a short post, so I’ll have to content myself with sharing some of the things he said to me over those years.)

In response to my question about why it took so long (from 1923 to 1938) for him to convince the British military that the jet engine was superior to the propeller, Frank thought for a moment and said: “My mistake was trying to sell jet engines to the men who made propellers.” You can interpret that in many ways, but to me it has always been a caution to remember that whatever it is you write, think, opine, or sell—your audience is every bit as important as your product. If a product doesn’t fit the mindset or preferences of your audience, maybe . . . just maybe . . . it’s not the product (or your writing) that is the problem: It’s the people you are peddling it to.

‘More haste, less speed!’ was one of Frank’s frequent comments. This one goes back to the ancient Greeks, and the notion is that while it’s important to work quickly, it’s detrimental to do so without prior contemplation and planning—and a willingness to refine and redo along the way.

When Frank was dying of cancer, his son Ian called me to say that Frank wanted to say farewell. This is what he said: “I want to thank you for being such a fine aide-de-camp all these years, Robert. Cancer is a bad business, but one must soldier on as best one can, mustn’t one?” Talk about a stiff upper lip . . . the old British grit that won World War II. I am inspired to emulate his example when—I hope not soon!—my time comes.

Photo credit: https://frankwhittle.co.uk

Mr. Paul Houser, my eighth-grade teacher. Mr. Houser looms large in my life because he was the person who turned me on to the power of the written and spoken word. Here are some of his gems of wisdom.

“Always define and clarify your terms.” You have to know what you’re talking about before you talk about it, let alone try to debate someone else. Too many people today talk about stuff they know nothing about. If you want to find out whether they do, ask them to define whatever term or terms they are using.

“What evil have I done that a fool commends me?” Mr. Houser’s wry sense of humor is on display here . . . if someone praises you, don’t take it without a grain of salt. You may be receiving complements from a nincompoop.

“Learning is suffering.” Suffering is a concept much out of fashion today. We have all sorts of entertainments, diversions, and drugs to keep us from feeling pain. And while some kinds of pain are indeed intolerable and ought to be assuaged, other types of pain (criticism, the difficulties involve in learning, failed attempts at doing something) are tutorial and salutary. If you accept that going in, you won’t mind the suffering so much. But if you tell yourself that things ‘should’ be ‘easier’ than they are . . . you’re in trouble. Anything that is worth doing well is NOT easy.

Once I asked him what he thought constitutes a ‘great teacher’. Without hesitation he replied: “A great teacher knows the material, loves the material—and, most important, loves the students.”

It is my great good fortune that I am still in frequent contact with Mr. Houser—we talk almost every week.

While that’s it for today, folks, I’ll be back with soon some learnings I gleaned from oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau and novelist Jack Salamanca.