Robert’s Ruminations: Tariffs and Income Taxes

Welcome to the new installment in a series on how the Gilded Age compares to modern times.

Today, something very topical: Tariffs.

Ever since my fascination (obsession?) with the Gilded Age began, I’ve been struck by the many parallels between their time and ours. It has been said ad nauseam that ‘history repeats itself’ or ‘history rhymes’ (whatever that means), but I tend to think that the similarities between historical periods are mostly due to the fact that human nature doesn’t change much over time.

So today I’m beginning a series of ruminations on how the Gilded Age compares to modern times. We’ll examine social customs, economics, and most anything that I think you’ll find illuminating.

Of course, I’m guessing what you’ll like, so if you want to hear something specific, feel free to suggest it by sending me a message.

Without further ado, then, the word of the day is TARIFFS.

There’s been a great deal of ink spilled recently about tariffs, but in the zillions of articles I can’t seem to avoid there are precious few that define the term itself. (My beloved eighth-grade teacher, Mr. Paul Houser, pounded into our heads that any discussion or debate must begin with the definition and/or clarification of one’s terms.) Let’s start there, then.

A ‘tariff’ is also known as a ‘duty’ or surcharge added by a country’s Customs bureau on some or all goods imported from another country. This money is remitted directly to the US federal government, and becomes a source of tax revenue.

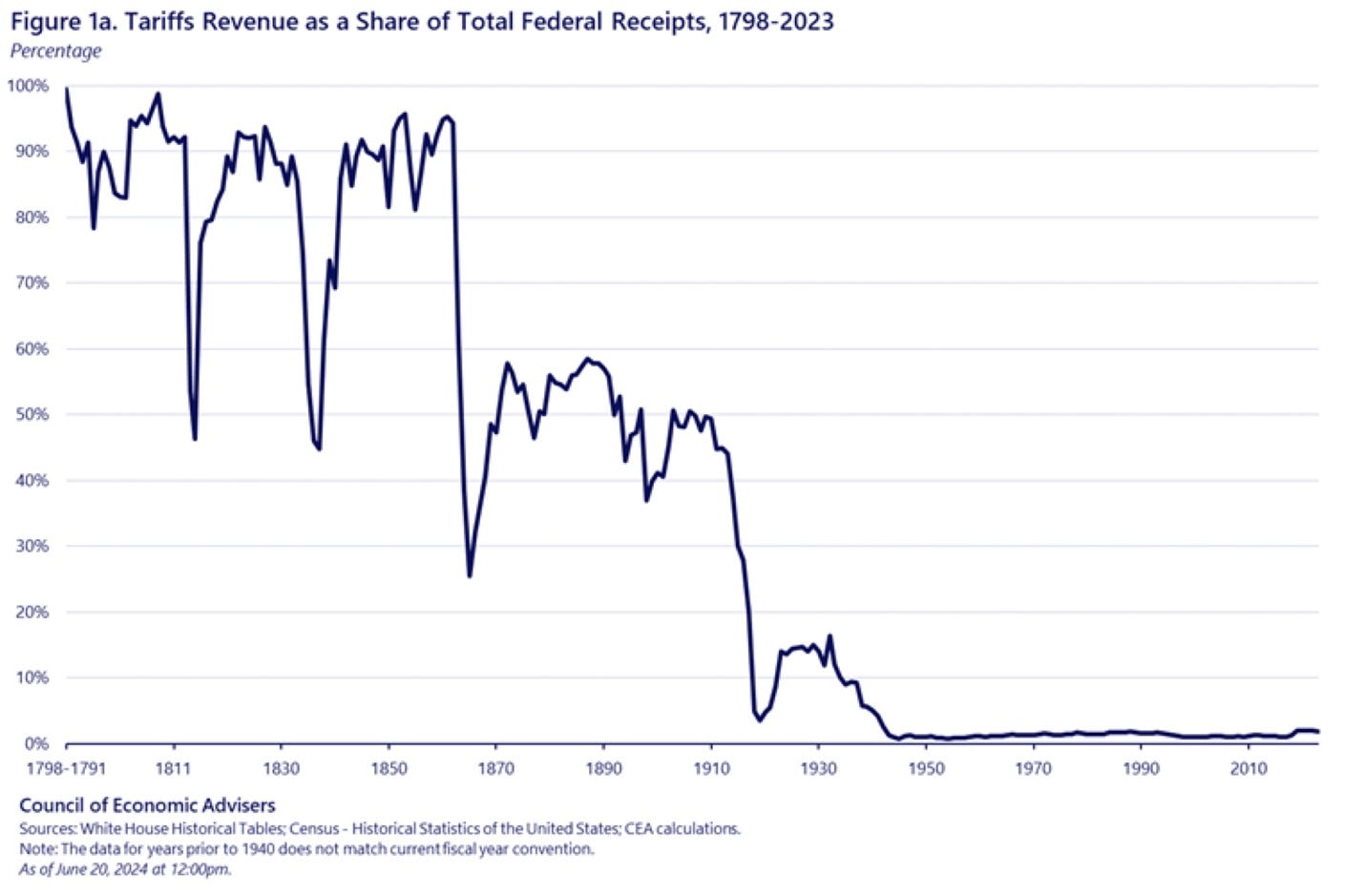

Tariffs have been in place a long time, both in the US and most everywhere else, but their importance to the United States has diminished dramatically over time. In the Gilded Age—roughly from 1870 to 1900—tariffs accounted for some 40-50% of all Federal tax receipts. As of 2024, they represented only about 2%. Take a look:

What changed?

The Sixteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1913—that’s what changed. Here’s the entire text of the amendment.:

“Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.”

These few words made obsolete (or at least optional) much of the tariff regime that had existed since the nation’s founding, when nearly 100% of the country’s Federal revenue was from tariffs. Why tax foreign goods—which always creates howls of protest both from the trade partner and from the buyers of more-expensive foreign goods—when you can simply take the money you need directly from Americans’ incomes?

The result: Today about 50% of all Federal receipts—about the same percentage as supplied by tariffs in the Gilded Age—comes from personal income tax. (The rest comes from Social Security and Medicare taxes, corporate taxes, and tariffs.)

Thus the Sixteenth Amendment meant that, for the first time—other than a wartime tax levied in the Civil War—Americans would now fund the government based on their personal earnings (income tax) and not based on their personal consumption (tariffs on goods actually purchased).

As much as most of us dislike taxes, you may be surprised to learn that the Sixteenth Amendment enjoyed enormous public support. Why?

One thing that’s very similar between now and the Gilded Age was the desire to ‘soak the rich’, and so the progressive income tax (meaning an increasing tax rate based on earned income) was seen as a way to do just this. And the Gilded Age had its Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, and Morgans—who were no more popular then, or less the object of envy, than billionaires are today.

The other reason that people supported the Sixteenth Amendment is that income taxes were promised to be very small and only applied to high earners.

Here’s how it broke down in 1913.

Annual earnings under $3,000 (~$150K today) were taxed at 0%. Considering that the average annual wage for all earners in 1900 was a little north of $500 (~$25,000 today) that meant very few common folk paid any income tax at all. The tax rate inched up a little at a time in lockstep with income until topping out at 6% on earnings over $500,000 (~$25 million today).

Today’s Federal marginal tax rates begin at 10% (joint incomes from zero to $23,200) and top out at 37% (joint incomes over $731,200).

An average Gilded Age worker, therefore, living today would pay a trifle over 10% of earnings in Federal income tax—whereas in 1913, as noted, that worker would have paid nothing. An earner in the top Gilded Age ‘soak the rich’ bracket (6% marginal tax) would now pay 35% on the same income, with one more bracket waiting should he or she have a good year.

It’s worthy of note that today’s average worker (joint income of about $80,000) pays a greater percentage of income to the Federal government (22% marginal income tax) than the ultra-rich did in 1913 (at 6%).

At least the rich can take some comfort that they were not the only ones soaked.

Since people haven’t become stupid in 112 years, I will speculate that if today’s Federal prevailing income tax rates had been floated in 1913, there would have been very little support for the Sixteenth Amendment. Over more than a century, Americans have simply gotten used to the ‘new normal’ of funding their government out of their incomes, rather than from tariffs charged on the goods they purchase.

The Sixteenth Amendment gave the Federal government an easy way to raise enormous sums—from a captive audience. Raise tariffs, and citizens have two basic choices: buy imported goods at the higher price or buy something else. Raise income tax, and citizens also have two choices: pay it without question or go to jail. That’s what’s called in metaphorical circles as a “Hobson’s choice,” by the way (look it up if you don’t know it—it’s a useful concept).

Which is better, then, tariffs or income taxes? You’ll have to make up your own mind on that; I honestly don’t know. What I do know is that the ‘tariff era’ of US history lasted from 1783-1913 (130 years), and the ‘income tax era’ has thus far lasted 112. Whether we are on the cusp of a third ‘era’ of taxation remains to be seen, but any way you slice it, it’s an interesting time to be alive.