Gilded Age Halloween: Then and Now

Think Halloween’s always been costumes and candy? Think again.

Discover the opulence, oddities, and eerie elegance of Gilded Age Halloweens—and contrast that with how we celebrate today.

If we were to travel back to October of 1900, we would find Americans were preparing for Halloween—but not with the high-fructose frenzy we know today. Instead, Halloween during the Gilded Age was an intriguing blend of old-world superstitions, parlor games, and a rising wave of mischief—all of which hinting at the more commercial, costume-heavy holiday of more recent times.

New Halloween Traditions and Inspirations

The Gilded Age ushered in a new way to celebrate Halloween. In 1900, Halloween was still heavily rooted in its ancient Celtic and European origins. Halloween night was seen as a liminal time—a ‘hallowed evening’, which became ‘Hallowe’en’ and then lost the apostroophe—when the veil between the living and the dead grew (perilously) thin. And it should be noted that Spiritualism, a quasi-religious movement (some might say ‘craze’), was sweeping the nation at this time. One of Spiritualism’s main tenets included the ability to communicate with the dead through séances and such other (sorry) tomfoolery as spectral emissions of a filmy substance called ectoplasm. (Yes, ectoplasm long predates the Ghostbusters crew!)

Gilded Age Halloween departed from the previous tradition of observing an All Saint's Day— which primarily involved visiting the gravesites of deceased loved ones. People of the day tended to subdue the more eerie or ghoulish practices so that Halloween fit more comfortably in a society concerned with morality, temperance, and quiet socializing.

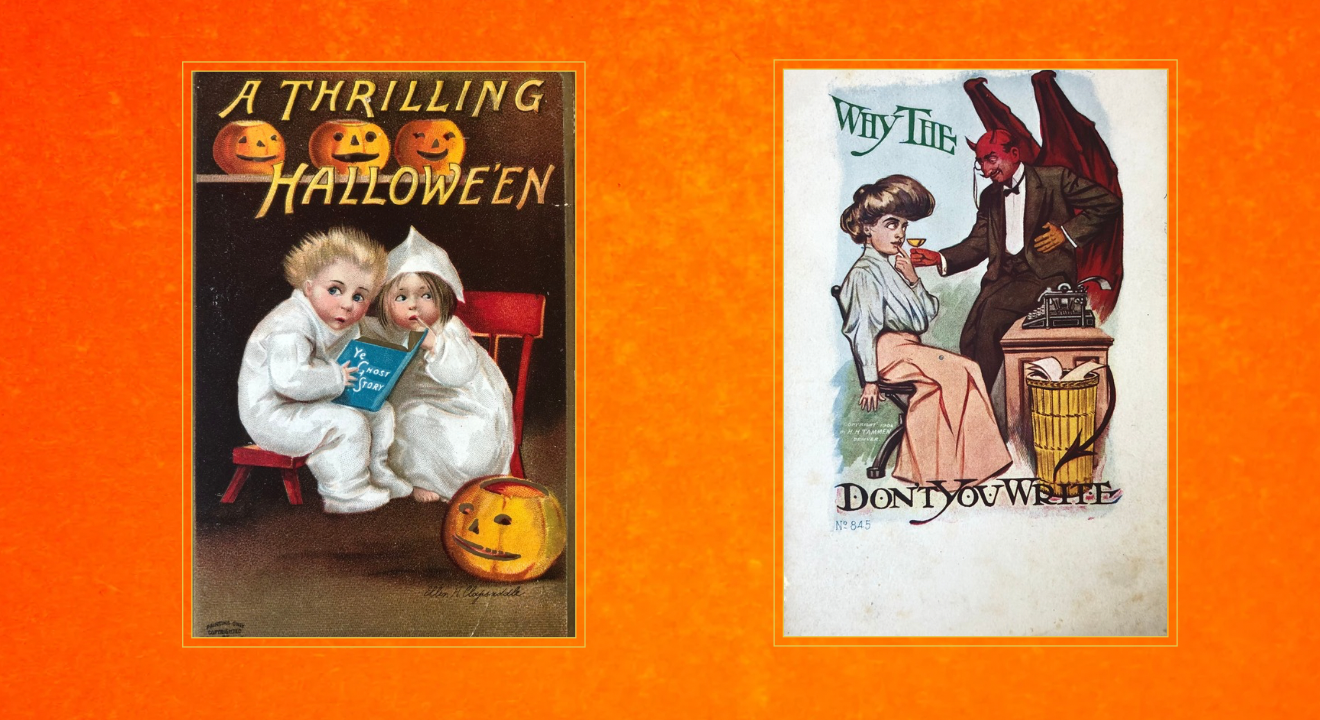

Popular periodicals of the time, though, helped reposition Halloween as a night for frivolous divination games and socializing with friends. Like today’s influencers, these magazines (Harper’s Weekly, The Delineator, and many others) promoted Halloween parties, games, recipes, and decorations. Invitations were often elaborate, hinting at the sort of party to come. Guests would dress in their best clothes and costumes, as the parties also served as a matchmaking opportunity.

A Night of Spirits and Superstitions

What transformed Halloween from a day of quiet contemplation of our mortality—into a night of lavish partying with games?

The answer is ‘romance’ (which still makes the world go ‘round).

Young women, in particular, looked forward to Halloween as a romantic holiday. A common ritual involved divination—when eligible women would playfully seek knowledge about their future husbands through games and contests. (Anyone remember saying ‘’S/he loves me; s/he loves me not’ while pulling the petals from a daisy?)

Apples, mirrors, and found objects were commonplace tools of the divination trade.

Apple peeling was a popular parlor game that consisted of, just like it sounds, peeling an apple in one continuous strip, then tossing it over a shoulder, with the hope that the peel would land in the shape of one’s future suitor’s initial. Or a young lady might peer into a mirror by candlelight at midnight on Halloween to catch a ghostly image of her future spouse.

Baking things with hidden objects inside was a common way to divine whether one might marry at all. A needle cake involved planting a single needle and a ring inside the cake before baking. Should a lady be served a slice with a needle in it foretold a single life, while a ring signaled marital bliss ahead. Fortunately, most of these games were only played for fun and not taken terribly seriously (and, we hope, any consumables were thoroughly examined prior to chewing).

Costumes and Merriment

Costumes did exist in 1900, but they were far more homemade and folk-inspired than today’s store-bought superheroes and pop culture icons. Children might dress as ghosts, vampires, witches, Gypsies, or animals using old sheets, papier-mâché, and whatever could be found around the house. Grownup ladies seemed to favor dressing as milkmaids or Marie Antoinette, and many gentlemen found Halloween a good opportunity to break out the old military uniform (if it still fit).

Rather than trick-or-treating, most people in the middle and upper classes spent Halloween night at masquerade parties. These events featured music, dancing, and games—especially including the hot new divination toy of the time, the Ouija board. Boys and girls might bob for apples, roast chestnuts, or play "snap-apple" (a game where apples are tied to a string and participants try to bite them without using their hands).

Tricks, Not Treats

Circa 1900, the "trick" part of Halloween was very real (and there weren’t yet many treats to balance it out). Mischief-making was on the rise, particularly among boys in rural towns and urban neighborhoods. Gates were lifted from their hinges, wagons were taken apart and then reassembled on rooftops, and outhouses were tipped over. Teens in particular were known to tie the doorknobs of neighboring apartments together, stringing ropes across sidewalks to trip pedestrians, and tossing bags of flour at well-dressed passersby. To the dismay of adults, the night became associated with youthful rebellion and minor vandalism.

As these pranks escalated in later years to include Incidents of arson and theft, communities sought ways to channel all that youthful energy into more organized and less destructive activities—leading to the later emergence of organized (and sanitized) trick-or-treating in the 1920s and 1930s.

So this Halloween, as you carve your jack-o’-lantern and don your costume, think about taking a glance into a mirror at midnight or whipping out the old Ouija board. And though there aren’t too many outhouses around to tip over these days, there are plenty of Porta-Potties—so those are best avoided on Halloween night, or you may find yourself bobbing for road-apples.