One Item, One Story

Sometimes focusing on a single physical object brings the past into clearer focus than a stack of documents. We can read about the Gilded Age in terms of industry, wealth, and rapid technological change—but holding or using an object from that era makes it more tangible. Its weight, materials, and wear tell a quieter, more personal story.

The Edison Triumph Model A Phonograph, produced around 1901–1902, is a useful example in enhancing our understanding of the time. Well documented through catalogs, advertisements, and surviving examples (one of which is in my home, lucky me!) it shows us how recorded sound entered domestic life at the turn of the twentieth century.

Physical Effort and Attention Were Essential

The Triumph Model A was a middle to upper class home phonograph designed for cylinder playback, and operated entirely by mechanical, hands-on methods. What does this mean, you ask? Great question.

To play music or recorded sound, one would wind the internal spring motor by hand, place a wax cylinder onto the mandrel, and lower the reproducer (which holds the ‘stylus’, or needle) to start the playback.

Maintenance and care were constant considerations. Wax cylinders were fragile and sensitive to heat, handling, and wear. Each playback slightly degraded the recording, so owners had to replace them when sound quality diminished. The machine itself required cleaning, occasional adjustment, and careful operation.

A hand-cranked spring motor powered the rotation of the cylinder, while sound reproduction depended on a stylus tracing grooves cut into a wax surface. The user’s role was active and continuous since the motor had to be wound before playback, the reproducer carefully positioned, and the speed monitored to ensure steady sound.

Cylinder recordings available during this period generally ran between two and four minutes. This limitation on duration was a technical detail—yet whether intentional or not, it shaped listening behavior. Music was consumed in brief bits rather than in a long stretch. Each cylinder represented a complete performance, and the act of changing recordings introduced pauses that structured the listening experience. These intervals required attention and encouraged interaction among listeners, as selections were discussed and chosen.

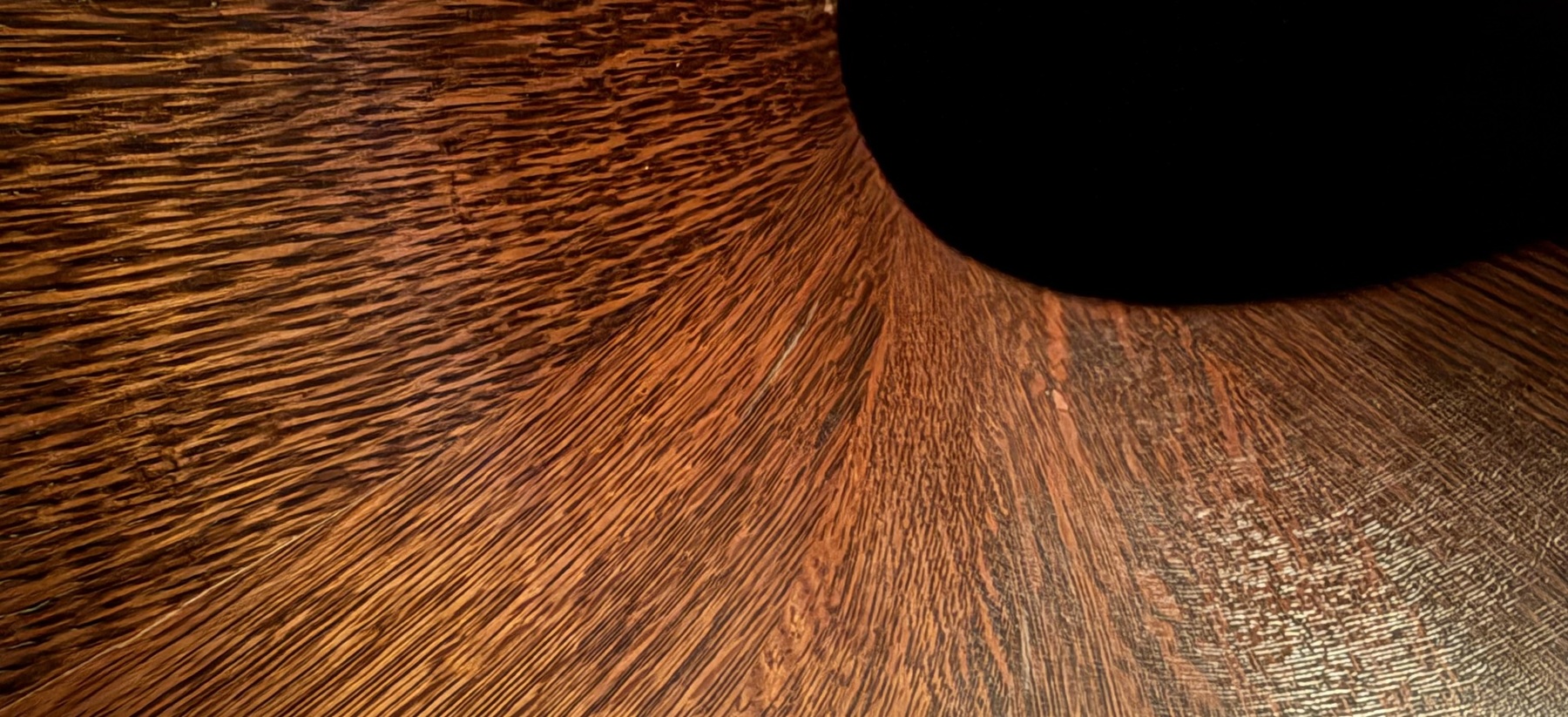

The Cygnet Horn

The particular phonograph we’re talking about today featured an Edison Music Master Cygnet Horn, which was constructed from multiple pieces of hardwood, often oak, which were carefully shaped and joined. Unlike simpler metal horns, wooden horns were marketed for improved tonal quality as well as visual appeal, since these machines were typically used in homes. Edison’s marketing literature of the period emphasized that wooden horns produced a “softer” and more “natural” sound, especially for vocal recordings. Their furniture-like appearance also helped them to become part of the overall appeal and decoration of the home, most usually placed in formal parlors for entertaining.

Owners played popular songs, spoken recitations, and novelty recordings for family members and guests. While dancing to phonograph music did occur, especially to marches and waltzes, the limited volume and brief recording lengths meant the phonograph functioned best in smaller rooms with listeners nearby. And aspiring musicians used the phonograph to learn new tunes by ear.

Cost and Context

Cost is an important factor in understanding how and where this machine fit into daily life. In 1902, the Triumph Model A sold for approximately $50, equivalent to about $2,500 today, not including premium accessories such as the Cygnet Horn. This price point was beyond the reach of many households, so ownership required both disposable income and an interest in new technology, though it did not necessarily imply great wealth. Edison marketed the phonograph as an attainable luxury—something aspirational but practical, and at a variety of price points (my example would be near the top of the range).

Despite its sophistication and appeal, the phonograph did not fully replace live music in the home. Families with the means still hired musicians for significant occasions. A string quartet, small orchestra, or vocalist provided volume, variety, and social prestige that mechanical reproduction could not yet match.

The phonograph instead occupied a complementary role—it provided reliable and repeatable entertainment on ordinary days and served as a sort of status symbol for guests who appreciated the latest and greatest things. It could be used without advance planning, allowing families to hear professional musicians and speakers repeatedly, at any time. Over time, this accessibility began to influence musical familiarity, taste, and trends. Repetition, which is a key feature of recorded sound, changed how people learned and remembered music. Listening was intentional, focused, and generally enjoyed by a group of people.

Fun Fact: In A Murder in Ashwood, you may recall a pivotal scene where Bert and Allie work to trap Penrose into a confession—with the help of their brand new phonograph. There’s a special treat for readers with an original illustration (one of three in the book’s interior plus the cover that my publisher commissioned) by the renowned scratchboard artist Mark Summers. See The Trojan Phonograph (Chapter 40).

If you haven’t read A Murder in Ashwood yet, I hope that you’ll give it a read. It’s been called “the ultimate turn-of-the-century murder mystery” that “has the feel of a great cocktail party.”